Unpacking the truth behind U.S. Treasury market volatility

Prasad Gollakota

20 years: Capital markets & banking

Was it really the result of basis trade unwinds?

What is behind the sharp and almost unprecedented volatility in U.S. Treasury securities since the announcement of U.S. tariffs and the furore it unleashed around the world? As you might imagine, there has been a lot of market chatter on this topic. One segment of the market that appears to have been blamed – yet again – in financial media and elsewhere for large outright moves up and down has been basis trading by hedge funds.

As is typically the case, however, this argument is wide of the mark. In this Insight, we explain the reasons, by delving into the ways basis trading really works.

Surge in Treasury yields

The current escalation in trade tensions, marked by the U.S. imposing substantial tariffs and subsequent retaliatory measures from China, has led to significant turmoil in the U.S. Treasury market, causing notable yield volatility:

- 10-Year Treasury yields: Surged by up to 22 basis points on 9 April, reaching approximately 4.5%, reflecting one of the most significant single-day increases in recent years. Earlier in April, by contrast, 10-year yields had dipped below 4% in a similarly-sized move the other way.

- 30-Year Treasury yields: Experienced similar spikes, briefly exceeding 5%, indicating a sharp decline in bond prices.

These movements are substantial, as Treasury yields typically exhibit more gradual changes. The sharp rise in yields signifies a rapid sell-off, with investors demanding higher returns for holding government debt amid increased uncertainty.

Beyond speculation: Getting to the facts

But the speculation, certainly in the media but also among certain market participants, that hedge funds, facing increased risks and potential losses from their basis trade positions, began liquidating their Treasury holdings to mitigate exposure and that this unwinding contributed to the selling pressure on Treasuries, which led to the surge in Treasury yields is, as mentioned at the beginning, wide of the mark.

To explain why, it is important to understand the dynamics of basis trades, as it highlights the interconnectedness of investment strategies and the broader financial market, illustrating how leveraged positions can influence market stability and government financing costs.

Revisiting the fundamentals

Let’s back up for a moment. Hedge funds aim to achieve high returns by employing various strategies, often involving significant leverage i.e. collateralised borrowing. Leverage allows these funds to amplify the size of their investment positions, and thereby their returns. In short, the idea is to borrow at a rate below the return they expect to generate from the investment. This approach also raises the risk profile, as losses can be magnified: if the expected return doesn’t materalise, funds are exposed to loss of capital. For this reason, hedge funds are perennially in the market trying to identify opportunities that offer substantial returns with little to no risk.

One such opportunity exists in the U.S. Treasury market, known as the basis trade . This is a one trillion dollar trading strategy that seeks to exploit the price difference between U.S. Treasury bonds (the actual securities) and listed Treasury futures contracts (agreements to buy or sell Treasury bonds at a future date).

The current volatile political, economic, fiscal and monetary environment has pushed bonds and futures out of alignment. Budget deficits are rising in many major economies and are expected to continue to do so, debt sustainability is a major concern, growth is stalling, and central banks are torn between raising rates to tame inflationary tariffs or lowering rates to stem any decline in economic output. That all leads to uncertainty, the one thing all markets hate.

In a basis trade, a hedge fund buys a Treasury bond and simultaneously sells a corresponding Treasury futures contract (i.e. has a short futures position). Or vice versa. Either way, the basis trader anticipates that the price gap between the two - known as the ‘gross basis’ - will shift in favour of the trader’s position over the horizon of the trade.

The gross basis represents the difference between owning the bond now or in the future. If borrowing rates are lower than current yields, a basis trader would prefer to own bonds now rather than later in order to capture the positive carry associated with owning the bond i.e. the difference between the interest received and the cost of financing the trade.

Think of basis trading as the combination of two factors: option value and carry. The basis trader has option value because the futures position generally offers up two options: when to deliver the eligible cash bond and which bond to deliver. Each bond future has a defined ‘delivery basket’ of cash bonds that can be delivered into the contract. The bond that is delivered will be the cheapest to deliver at the time of delivery. As for carry, value here arises when the trader can achieve a return above the cost of borrowing to finance the trade.

If the trader opts to run a short futures position and buy bonds, they will typically use repurchase agreements (repos) to finance the purchase, wherein the bond is used as collateral to borrow funds at a relatively low interest rate. Banks, broker dealers, money market funds and even pension funds and insurance companies might be on the other side of this repo trade. It’s a relatively safe position to take on for these parties, due to the strength of the underlying collateral.

Illustrative economics of the basis trade

You might be recalling your futures 101 where, in theory, futures are priced to eliminate arbitrage . This is known as the cost-of-carry model :

Futures price = Spot price + Carrying costs − Income from the asset

For U.S. Treasuries, this typically includes:

- The repo rate (cost of financing the bond)

- The coupon payments received (income)

In practice , though, small pricing inefficiencies exist — especially when there's market stress , liquidity mismatches , or limits preventing arbitrage (e.g. capital constraints, margin calls). That’s what allows trades like the basis trade to exist: they aim to exploit those small, temporary differences between the cash and futures markets, as mentioned often using leverage to amplify the return.

If the futures price were too far above or below this fair value, arbitrageurs would step in:

- Buying the cheaper instrument (bond or future)

- Selling the more expensive one

- Locking in a risk-free profit

If market conditions remain stable, the price difference between the Treasury bond and its futures contract narrows as the futures contract approaches its expiration date. The hedge fund can then close both positions, realising a profit from the convergence. Even in the absence of convergence, the hedge fund can simply go through the delivery process to exit the trade at a profit; i.e. earning the differential.

Here’s a theoretical example:

- Purchase of Treasury bond: Buy a Treasury bond for $1,000,000 with an annual yield of 2%.

- Sale of futures contract: Sell a futures contract corresponding to the same Treasury bond, priced slightly higher due to market conditions.

- Financing via repo: Use the purchased bond as collateral to borrow $1,000,000 at an annual repo rate of 1.5%.

Expected Outcome:

- Interest income: Earn 2% interest on the $1,000,000 bond, totaling $20,000 annually.

- Financing cost: Pay 1.5% interest on the $1,000,000 borrowed through the repo, amounting to $15,000 annually.

- Net profit: The difference between the interest earned and the financing cost is $5,000 annually.

Leverage

While the profit margins on each trade may be small, using leverage can turn modest price movements into significant gains: hedge funds can borrow as much as 100 times their initial capital to amplify tiny pricing differences between bonds and futures; meaning $10 million of capital outlay could in theory fund $1bn worth of exposure. Leverage that extreme is at the outer edges of where hedge funds are typically comfortable, but it’s not unheard of.

It’s this excess leverage coupled with the inability to post margin that creates exposure for the funds. Posting margin refers to the changing value of collateral that trading counterparties have to post to reflect the changing value of their trading positions. If market conditions turn volatile—due to factors like sudden or unexpected political or economic policy changes or geopolitical events—the price gap (or basis) may widen, meaning funds have to post more collateral. Hedge funds that are unable to post margin might face losses as they rapidly unwind their positions.

Funds that are too highly levered may not leave themselves with enough of a buffer of unencumbered available-for-sale liquid assets to be able to post margin. Unwinding involves selling the Treasury bonds and closing (or buying) the futures positions, actions that can exacerbate market instability. This action may not, however, necessarily cause significant divergence in the basis; i.e. the upward pressure in Treasury yield may be offset by the downward pressure in the futures price.

Digging in the wrong place

As explained above, basis trades are predicated on relative value where a trader either has a long position in a bond and a short position in the futures contract or vice versa. That being the case, they do not have direct exposure to outright moves up or down.

In other words, the basis trade is market neutral i.e. it neither represents an outright long or outright short position. Unwinding the trade by definition does not unload directional risk into the market. Theoretically, extreme volatility that leads to margin calls that in turn forces basis traders to sell bonds to raise the cash required might be an issue, but even then this shouldn’t be a factor for a market as deep and broad as the U.S. Treasury market. In that respect, Treasury volatility stems from the actions of outright position holders, not from margin trades unwinding. Put simply, it’s the dog wagging the tail, not the other way round.

Even if the bonds and futures moved a full point apart, that would push the trillion dollar basis trading market offside by 10 billion dollars. That’s a lot, but selling Treasuries to fund that additional 10 billion dollars in variation margin is a drop in the ocean relative to the 27 trillion Treasury market.

And even if the Treasury market is technically mispriced, basis trades are unlike other relative value trades or macro trades in that the mispricing is resolved every three months as futures delivery takes place quarterly, so basis traders can simply receive or deliver bonds and iron out the mispricing. As such, the market tends not to remain mispriced as delivery approaches.

As multiple commentators continue to extol the dangers of the basis trade, what springs to mind is Indiana Jones dramatic realisation in Raiders of the Lost Ark, “They’re digging in the wrong place.”

This insight was originally authored by Prasad Gollakota, with editorial contributions and reviews by Keith Mullin.

Prasad Gollakota

Share "Unpacking the truth behind U.S. Treasury market volatility" on

Latest Insights

UBS and Switzerland: Capital hikes are not the right tool for the job

15th October 2025 • Prasad Gollakota

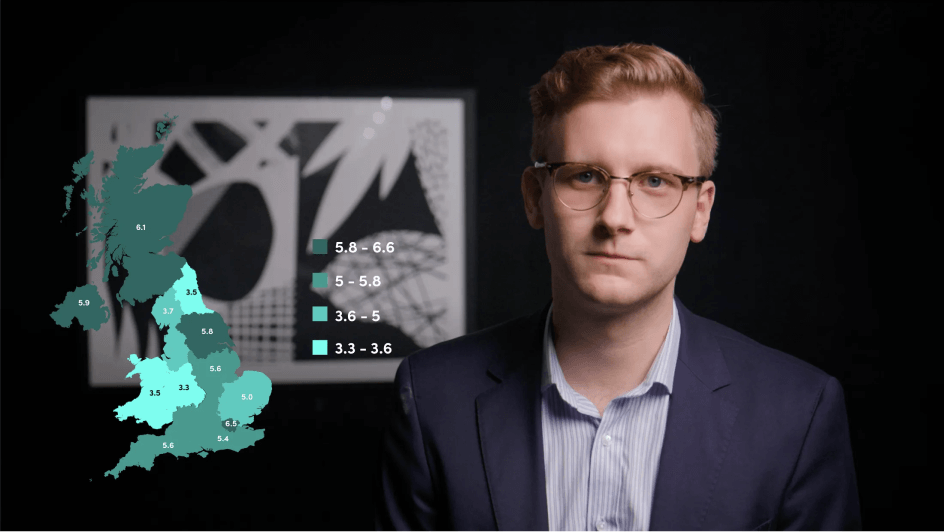

Trade deals & trade wars: The regional impact

23rd May 2025 • Adrian Pabst and Eliza da Silva Gomes